—-

To stay in the loop with the latest features, news and interviews from the creative community around licensing, sign up to our weekly newsletter here

Set Designer Tim McQuillen-Wright reveals the secrets of enhancing immersive experiences.

You’re a busy, man Tim! We’ve been trying to align our diaries since we first met seven years ago… But no pressure!

Oh, gosh! After all this time, I do feel obliged to have something interesting to say – and I’m not sure I do!

Ha! Well, I beg to differ… You have an enormously interesting perspective on immersive brand extensions. But on that, how do you describe yourself?

I still call myself a theatre set designer, although – for the last eight years or so – my career has been 90% immersive theatre. Well… I used to call it immersive theatre. Now, it’s probably more accurate to call these shows immersive experiences. That’s just me, though: I don’t think the industry necessarily makes a distinction as regards what the differences are.

What are the differences? What does immersive mean?

Some people think immersive means you take away the audience’s seat and ask them to pay double! Ha!

Ha! Very good! Ha! So to orientate ourselves, can you tell me a few of the properties for which you’ve designed immersive sets?

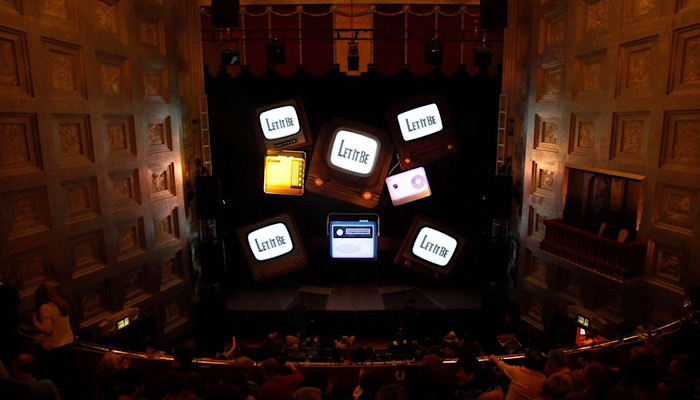

Crikey. There’ve been quite a few now. Let me see… War of the Worlds, Gunpowder Plot, Monopoly Lifesized, I’ve done quite a few for Secret Cinema: Moulin Rouge, 28 Days Later, Stranger Things… In more traditional theatre, I’ve done Spamalot, The Wizard of Oz, Let It Be… I should’ve made a list!

Oh, I think it’s more interesting to see what pops to mind! Before we talk about licensing, I want to ask about something you said once… That for some people, all immersive can be terrifying. How so?

Well, first, this isn’t a criticism of the genre because a lot of immersive stuff is absolutely amazing. What I mean to suggest is that some immersive can be uncomfortable and terrifying to an audience… You don’t know whether there’s going be audience participation, for example. You don’t know whether you’re really safe or whether you’ll be brought in to play a role – which I personally would find agony. And the discomfort is often there because it can be tricky to explain the show without giving too much away…

And it’s possible, I suppose, that the director might want the audience in a flop sweat as part of the experience…

Yes, the whole point of these things is that the unknown is around every turn. So do we – as the creative team – want to be giving away at the beginning that no one’s going to talk to you as if you’re a character? Does it help the show for you to know no one’s going to come along and ask you to do your favourite dance moves, or whatever?

The metaphor that springs to mind is swimming. You’ve got those who stand on the shore and dip their toe in. You’ve got those who paddle, those who swim and those who dive… But, of course, we need to cater to all those people even though the focus might be the biggest group; the middle groups.

But is it self-selecting to some extent? If we take horror, for example, I’m enormously – well, I think squeamish is too weak a word… I’m hagridden in the audience…

Hagridden?

Yes; I can’t face the agony, as you put it, of any horror – or anything designed to make me feel awful. I’m wondering, then: is THAT the set designer’s job? To help manipulate the audience into feeling emotions that relate to the IP?

Oh, yes! I wish I’d articulated it like that… Absolutely! In immersive, my role is to create backgrounds or environments that help evoke feelings. Manipulation sounds like a bad word, but ultimately, that is what we do. We’re trying – at the very least – to nudge your emotions in the right way. That’s also true with conventional theatre but, as a jobbing designer, I don’t always get the same opportunities there.

Because traditional theatre sets tend to be more of a backdrop? More passive?

Right. A theatre set helps make it happen without anybody being aware of the mechanics of it, I suppose. But in the immersive world, it’s a lot more present. And I haven’t really dissected this, but I wonder whether part of it is because, with immersive, the money doesn’t go as far. Everything is more expensive because the audience is so much closer to it physically; oftentimes they can touch it – it needs to be much, much more robust.

I hadn’t thought about that. You can get away with murder on stage! So the closer the audience is, the more money you’re likely to have to spend?

If they’re closer, yes, and if they can touch it. And it’s dramatically more expensive, Deej; as much as ten times the cost. Keep in mind that we’re also trying to cover a massive space for immersive, much bigger than in a theatre. So the scenic has to do a lot of heavy lifting in terms of the storytelling beats… Everything has to pay its way in terms of delivering an emotional response as well as locational information, and there needs to be a real cohesion to it. The audience shouldn’t know the information they’re being given.

The audience shouldn’t know the information they’re being given by scenic?

Yes; to some extent it should be a thankless task! The scenery’s not the sort of thing we can ask people to fill in a questionnaire about at the end! We can’t ask, “How important was this piece of design?” because it should feel like it wasn’t important at all! By way of example, I worked on something recently, which I shouldn’t divulge too much about, but it’s pretty epic in scale. There was a sequence near the start designed to pulse the audience through a period of time during which things go a little crazy…

This sequence took a month of design with an assistant and me churning out sketches, visuals, models – all sorts. But it only really worked when we had an audience of a specific size… Because if a group is too small, the people in it can be too self-conscious. For this, we had a bigger group and a bigger sequence – but as it came together it felt too big; too much theatrically speaking… You don’t want to put all your money and energy into a moment that happens in the middle of act one. So we eventually made a creative decision to cut the whole thing.

Oh, that sounds painful! Did it feel right to cut it, though?

It did, actually. But you’re right, it was painful. We tried other things to make it work because, as you know, you explore every opportunity… You keep hoping some epiphany will happen: “What if we moved it here? What if we did this? Or that?” You sometimes have a voice in your head telling you that you know it’s got to go even if – in your heart – you don’t want it to.

I know exactly that feeling! Tell us a little about your process, Tim. Someone comes to you to work on a brand experience… How do they communicate the brief?

With devised shows, trying to figure out what the brief is really matters… What IS the show? What’s the essence of the IP? What do we want the audience to feel at the end? What should be the overriding memory? What feeling should audiences have at certain times? What touch points do we have to include? Most of that still needs to be worked out when I first get involved – but it’s all verbal! Whereas, when you’re doing a play, you do at least have a script as a starting point.

So you discuss it; the brief – such as it is – is verbal. What happens next?

With immersive, I tend to do sketches rather than physical models because there’s not time to do what we’d do in traditional theatre. So I scribble a few ideas – but even this has changed over the last eight years… It used to be all pencil sketches, then it became pencil with colour. Then, for some shows I would do big marker drawings.

Oh, really?!

Yes! You know, I love the work of Syd Mead – he described himself as a ‘visual futurist’… Amazing work. Also, the Bond designer, Ken Adams… Oh, my God! His drawings are so energized and amazing; you can see the speed at which they’ve been produced – which is the important bit… Because in immersive, there’s no time at all. You just get an idea out there: approved or rejected; do another…

But the work Ken Adams did was just beautifully epic. I read a book on him which, for the most part, was a series of interviews… He said he’d been drawing with a pencil for a long time, but then basically retrained himself to draw with a big marker… That way, he doesn’t get bogged down in details. And I thought: if Ken Adams has the humility to retrain himself to draw like that, who the hell am I to say I can’t?!

So a big, thick pen physically stops you getting sucked into too much detail? That’s a breathtakingly simple technique. It’s great!

It’s absolutely amazing! So you can imagine, when I did the Secret Cinema Blade Runner, all those sketches were done in big marker pen. Anyway, in terms of the process, after those scribbles, that proper sketching period comes very early. As soon as it starts to land, I get my assistant to turn that into a very basic SketchUp model, which gives a better sense of the space. Then I start putting in detail as a way of trying to figure out a storyboard, in effect, of a journey through a piece…

Quite often, I’ll draw over it to get the spatial accuracy close because – with most directors; most people, actually – it’s hard to communicate how much space is in a drawing. You need to include a reference point… If you know that a doorway is spatially accurate, say, then you might have enough guiding points to contextualise what you’re talking about.

I’m interested in the speed with which all this happens. At what point do things lock off? At what point does one say, “Okay! No more changes! We open in 15 minutes!”

Ha! You joke… But with the devised experiences, it changes right up until we open – sometimes after! On Blade Runner, we cut a third of the experience after the first public performance – no exaggeration.

Oh, good LORD! What got cut?

The storyline was that, as one of the wealthy people, you had a ticket to leave this world and go off world to the utopian planets. So we created this spaceport… You’d go in with your ticket ready to leave, then you found out that there’s a problem. You had to go into this room… And you’d basically be sent away from this gleaming white spaceport in a lift that took you down and spat you out in dystopian LA. And then the more familiar Blade Runner experience would start. But after that first public performance, the creative director just went, “It’s not actually working, is it?”

Wow! That’s gutsy! And, actually, that perfectly lines a question I wanted to ask… It seems to me that a creative team is always picking up a poisoned chalice when it comes to expanding or interpreting established IP…

How so?

Well… You, your team, your director: you’re all going to be saying something to the effect, ‘We need to hit these beats because everybody is expecting them…’ Right? Because the audience would be disappointed if there wasn’t enough of the original IP…

Right…

But, at the same time, you’re aiming to give everyone a new experience; something fresh. To me, that seems like a poisoned chalice.

I see! Yes, you’re right; you’ve got to do both. And that can be a tightrope walk. One of the branded experiences which I’m really proud to have been involved with is Stranger Things…

For Secret Cinema?

Yes. For all the stress and effort from the blank piece of paper at the beginning to the end result, that project was very pleasing. I loved the whole show. But there was a point in it when I had the idea to give the audience an Easter egg; a little reference to the original IP. I thought the map from season one was so iconic that we should give a nod to it. So we created a version of it in an on-site bar – so it wasn’t ‘in universe’, but it was part of this experience in a bar where the rules are slightly eased anyway because people are paying with contactless, they’re together with others – it’s separate from the full immersion.

I get it… It’s universe adjacent rather than in-universe.

Right. People often want to take bit of a break from full immersion. They’re grabbing a drink, talking about the show…

And you’re giving them an environment with an iconic image on the wall as a flavour of the show?

That was my thinking, yes… That we use this imagery as a way of describing all the things around the site that people might not have found. I thought it was nice. I had a few art-department folk drawing this thing for a couple of days… When the director saw it, he just said no – because it wouldn’t exist in this world.

Ouch! And I’m curious: was he right?

Yes, he was absolutely spot on. As soon as he said it, I just went, “Oh, God! Yes.” It’s not a theme park ride, you know? So I’d been trying to give the audience that Easter egg… But actually, unless we were doing that scene, or fully planting people in that space, that thing shouldn’t exist there. I guess there could’ve been a storyline that gave it a reason to be there… But we hadn’t created that! I shouldn’t have put it in the space. And I’d like to think that I wouldn’t have made that kind of error, but I did.

You’re very honest about that, Tim – which is rarer than you might think! Now, we do need to start wrapping this up… I meant to ask at the start, though: how did you come to be doing immersive theatre?

The first immersive thing I did was 28 Days Later for Secret Cinema. Looking back, it was nuts. But it was a great thing to do – the perfect starting project.

Oh, really? I would’ve thought that would be enormously intimidating.

Oh, it was! Ha! It was intimidating, ridiculous and nuts. But I think those companies, at that time, kind of built ‘ridiculous’ into their DNA. Ask yourself: ‘Why would any company try and stage an event like that?’ I think the answer is simply that no other company would’ve dared. That was part of the joy! And I think Secret Cinema at that time had that as part of their make up, too…

That sense of pluck, you mean?

Yes, the boldness to attempt it was part of the audience’s joy. But to your question… I remember, as part of the interview process, that I was asked to go to their previous show. I enjoyed it but was quite taken aback! There was an intense number of ideas, so I knew immersive would be a big undertaking. I didn’t know exactly what the show was at the point when they asked me talk to the creative director, either.

To clarify, you’d been recommended, right? Someone had told them you were a genius?

Gosh, I very much doubt anyone said that! But yes, they said, “We’ve been told to talk to you.” So I went and spoke with the creative director and found out it was for 28 Days Later… I said I hadn’t seen it in a few years but that I knew it and enjoyed it. And they said, so are you up for this? And I said, “Yes, if the dates work; absolutely. When does it open? And they said, in four weeks.”

Oh, they did not?! 28 days later? Ha!

Ha! Yes, indeed. Absolutely insane. Ha! But, to be fair, they’d done it so often before… But I think I said I didn’t know how it could work; that it sounded insane. Then I went and spoke to the production manager, whom I knew anyway, which was something of a bonus. And he said that I could bring in my own team and they’d find me an art-department team: you start sketching, we’ll start building! And that immediately made it feel more manageable.

Golly. And that four-week turn around… Did that make things leaner in terms of ideation? Or did you just keep coming up with idea after idea after idea to see what stuck?

Hmmm. With all these shows, the reality is that ten times more ideas get cut than stay. And they can get quite progressed, too. At times, the build drawings are done, you’re about to confirm with a set-building company – and then the storyline can change entirely. Absolutely nothing’s set in stone…

And actually, as you may know, I don’t use social media very much. Maybe twice a year, though, I put up, on Instagram, a load of visuals and sketches of things that never made it. Personally, I find putting up stuff that didn’t happen more interesting than putting up stuff that’s sort of self-congratulatory!

I quite like that! Because if you’ve toiled over something that gets cut, it’s still great to see the art behind it. And to finish off then, Tim, is there a question I could have asked you today that I didn’t?

Gosh, no, I don’t think so… You mean is there anything I’d quite like to have been asked?

Yes, you could phrase it that way…

Well, no. I don’t – as you know – I don’t relish being interviewed at all, so I certainly didn’t walk in hoping you’d ask about something specific because I’ve got a sound answer to it! Ha! I walked in going, ‘Oh, God! I hope I get away without saying anything utterly ridiculous.’ So I can’t think of anything, no.

And out of interest, do you think you got away with it?!

Ha! I can’t remember saying anything staggeringly idiotic. There might’ve been something mildly idiotic, but that’s fine. Do you think I got away with it?

I think we both got away with it! And I can’t thank you enough, Tim. I began to suspect you weren’t crazy about interviews after year three of me hounding, so I’m very grateful that you made time for me. Thank you again.

Enter your details to receive Brands Untapped updates & news.